“We will ask for estimates and then treat them as deadlines.”

Estimates are typically a necessary evil in software development. Unfortunately, people tend to assume that writing new software is like building a house or fixing a car and that as such the contractor or mechanic involved should be perfectly capable of providing a reliable estimate for the work to be done in advance of the customer approving the work. With custom software, however, a great deal of the system is being built from scratch, and usually how it’s put together, how it ultimately works, and what exactly it’s supposed to do when it’s done are all moving targets. It’s hard to know when you’ll finish when usually the path you’ll take and the destination are both unknown at the start of the journey.

I realize that estimates are a hard problem in custom software development, and I am certainly not claiming to be the best at producing accurate estimates. However, I have identified certain aspects of estimates that I believe to be universally (or nearly) true.

Estimates are Waste

Time spent on estimates is time that isn’t spent delivering value. It’s a zero-sum game when it comes to how much time developers have to get work done – worse if estimates are being requested urgently and interrupting developers who would otherwise be “in the zone” getting things done. If your average developer is spending 2-4 hours per 40-hour week on estimates, that’s a 5-10% loss in productivity, assuming they were otherwise able to be productive the entire time.

A few years ago, a Microsoft department was able to increase team productivity by over 150% without any new resources or changes to how the team performed software engineering tasks (design, coding, testing, etc.). The primary change was in when and how tasks were estimated. Ironically, much of this estimating was at the request of management, who, seeking greater transparency and hoping for insight into how the team’s productivity could be improved, put in place policies that required frequent and timely estimates (new requests needed to be estimated within 48 hours). Even though these estimates were only ROMs (Rough Orders of Magnitude), the effort they required and the interruptions they created destroyed the team’s overall productivity.

Estimates are Non-Transferable

Software estimates are not fungible, mainly as a corollary to the fact that team members are not fungible. This means one individual’s estimate can’t be used to predict how long it might take another individual to complete a task.

The transfer ability of estimates is obviously improved when the estimator and the implementer have similar experience levels, and even more so when they work together on the same team. Some techniques, like planning poker, will try to bring in the entire team’s experience when estimating tasks, ensuring estimates don’t miss key considerations known to only some team members or that they’re written as if the fastest coder would be assigned every task. This can help produce estimates, or estimate ranges, that are more likely to be accurate, but it does so by multiplying the time spent on estimating by the entire team’s size.

Estimates are Wrong

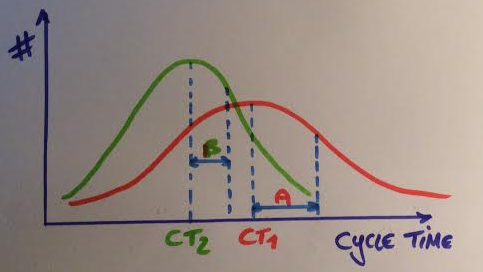

Estimates aren’t promises. They’re guesses, and generally the larger the scope and the further in the future the activity being estimated is, the greater the potential error. This is known as the Cone of Uncertainty.

Nobody should be surprised when estimates are wrong; they should be surprised when they are right. If estimates were always accurate, they’d be called exactimates.

Since smaller and more immediate tasks can be estimated more accurately than larger or more future tasks, it makes sense to break tasks down into small pieces. Ideally, individual sub-features that a user can interact with and test should be the unit of measuring progress, and when these are built as vertical slices, it is possible to get rapid feedback on newly developed functionality from the client or product owner. Queuing theory also suggests that throughput increases when the work in the system is small and uniform in size, which further argues in favor of breaking things down into reasonably small and consistent work items.

Estimates of individual work items and projects tend to get more accurate the closer the work is to being completed. The most accurate estimate, like the most accurate weather prediction, tells you about what happened yesterday, not what will happen in the future.

Estimates are Temporary

Estimates are perishable. They have a relatively short shelf-life. A developer might initially estimate that a certain feature will take a week to develop, before the project has started. Three months into the project, a lot has been learned and decided, and that same feature might now take a few hours, or a month, or it might have been dropped from the project altogether due to changes in priorities or direction. In any case, the estimate is of little or perhaps even negative value since so much has potentially changed since it was created.

To address this issue, some teams and development methodologies recommend re-estimating all of the items in the product backlog on a regular basis. However, while this does address the perishable nature of estimates, it tends to exacerbate the waste. Would you rather have your team estimate the same backlog item, half a dozen times, while never actually starting work on it, or would you rather they deliver another feature every week?

We know that estimates tend to grow more accurate the later they’re made (and the closer they are to the work actually being done). Thus, the longer an estimate can be reasonably delayed, the more accurate it is likely to be when it is made. This ties in closely with Lean Software Development’s principle of delaying decisions until the last responsible moment. Estimates, too, should be performed at the last responsible moment, to ensure the highest accuracy and the least need to repeat them.

Estimates are Necessary

Despite of all the drawbacks, estimates are often necessary. Businesses cannot make decisions about whether or not to build software without having some idea of the cost and time involved. Service companies frequently must provide an estimate as part of any proposal they make to build an application or win a project. Just because the above words are true doesn’t magically mean estimates can go away. However, one can better manage expectations and time spent on estimating if everybody involved, from the customer to the project manager to the sales team to the developer, understands these truths when it comes to custom software estimates.

Conclusion

If you’re in a position where you want a reliable estimate for a software project, and you’re having a hard time getting one from your developer/team, remember this quote: “You can’t find someone who knows how long this will take, but you can probably find someone who will lie to you.”

Essentially: The more difficult it is for you to get an estimate, the more likely it is that when you finally do, it’s not terribly accurate.